This is the first guest post for a while here. Today Dr Vivian Allen of the Royal Veterinary College in London, an expert on dinosaur locomotion, discusses a recent paper that attached weights to the back of chickens. There’s a good reason for it, honest …

Recently, a bunch of my fellow dinosaur scientists spent considerable time and effort making little model tails out of wooden sticks and clay, and then Velcro-ing them to chickens’ bums. More-or-less just to see if it made them walk funny. This is the kind of easily lampoonable research that, to the casual observer, makes it seem like people in my profession are a bunch of time-wasters. Your tax money hard at work, ladies and gentlemen! Ha, look! Look, see. We videoed it. The chicken does walk funny when you strap a bunch of stuff to its bum. We were right! Nobel prize, here we come!

However, they don’t generally let actual idiots be scientists, and so, like most research, this chicken-bottom manipulation was done by serious, clever people for serious, interesting reasons. By attaching things to chickens, Dr Bruno Grossi and colleagues were attempting to solve a particularly thorny scientific problem – how did having such a large, heavy tail affect the way dinosaurs walked around?

Attempting to study walking and running in extinct animals such as dinosaurs can be frustrating. Movements do not generally fossilise (barring the odd footprint), so we are heavily reliant on comparisons with living relatives. As has been known for decades, modern birds are dinosaurs (even comparatively rubbish birds like chickens). So, the way birds – living dinosaurs – move is obviously a vitally important source of data for understanding how locomotion worked in extinct dinosaurs.

But birds have some unusual features that set them apart from all the other dinosaurs. A major difference is that birds don’t really have tails, or if they do, they’re fairly naff, feathery things. All the other dinosaurs had a really big, long, meaty tail. So, somewhere on the way to birds, the tail became so reduced in size that it has almost been totally lost.

The way birds move is also quite idiosyncratic. The vast majority of land animals, including ourselves, move forwards by swinging the entire leg back-and-forth from the hip (hip-driven locomotion). However, birds keep their hips extremely bent, pointing their thighs forwards, and move around mostly by swinging the (very long) lower leg from the knee (knee-driven locomotion). This bent hipped, knee-driven style of moving gives them a characteristic “crouched” look, and requires using the limb muscles in a fairly different way to a more hip-driven style.

So, the living dinosaurs are a bit weird in terms of locomotion. Does that mean all dinosaurs moved like this? Well annoyingly, probably not. As Grossi and team’s research (among other work) shows, the way birds move is most likely related to the fact they have lost their ancestral tails.

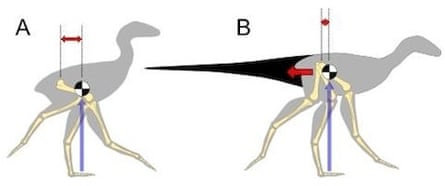

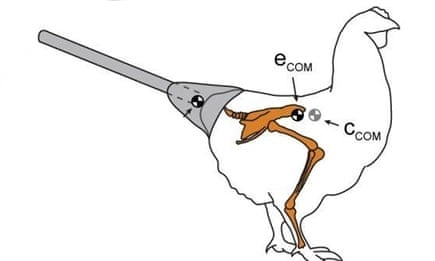

A tail represents a large chunk of mass stuck on the back of a dinosaur. Losing it changes the way the mass of the body is distributed, which thus changes the position of the centre of mass (AKA centre of gravity). This matters for locomotion because in order to remain balanced, the forces that the dinosaur makes with its feet to support and move its body have to point more-or-less straight at the centre of mass. So the position of a centre of mass has a large amount to do with where a moving animal puts it feet and legs.

Losing the tail means that relatively more of a bird’s mass is at the front of the body, resulting in a more forwards centre of mass. To remain balanced, the feet and legs also need to be placed further forwards. And, one consequence of the crouched, knee-driven way birds walk and run is that the leg joint that does most of the job (the knee), can be stuck a lot further forwards on the body than the main joint other animals use (the hip). So a lot of the weirdness of bird locomotion may just be related to them having to put their legs more towards the front of the body, to match the centre of mass.

But dinosaurs with tails would have had a centre of mass further back on their bodies. Would they have moved using their knees as well? Or would they have moved in a more straight-legged, hip-driven way, like most other animals? Standing with straighter legs would place the knee and feet further backwards, matching the centre of mass, allowing the whole limb the freedom to swing back and forth. So in theory, it seems plausible that they would be more hip-driven.

However, the biology of locomotion is intricate, comprised of a frankly bewildering amount of complicated things, all interacting – bones, joints, muscles, tendons, ligaments, nerves, brains, the whole paraphernalia. It’s hard to predict exactly how a complicated system such as locomotion will respond, even to relatively simple changes in centre of mass position.

Unless, as Grossi’s team have done, you simply take that complicated system and stick a big tail on its bum. And, almost anticlimactically, they found exactly what our simple theories predicted – the false tail moved the centre of mass further back, and the chickens responded by straightening their legs and swinging their hips more. Chickens wearing dinosaur tails become less knee-driven like other birds and more hip-driven, like most other land animals! It’s a simple thing, but it gets professional nerds like myself excited. It implies that we can use a simple concept like centre of mass to make predictions about a very complicated thing like locomotion.

The current trend in this kind of research is towards more and more technical methods, trying to reconstruct movement using highly detailed computer models of extinct animals, every muscle, tendon and bone simulated. While this technical progression is undoubtedly a good thing, and will eventually allow us to answer some very interesting questions about dinosaurs (how a six-tonne biped like a tyrannosaur turns a corner, for instance), it is refreshing to see such a conceptually simple, experimental analysis as this bear fruit.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion